|

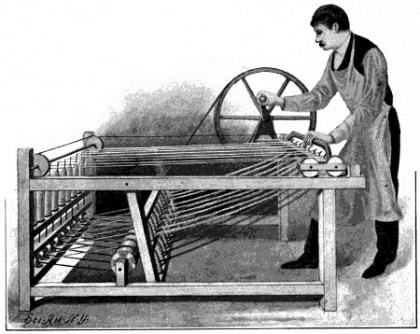

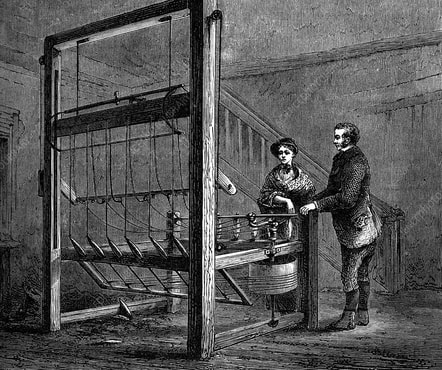

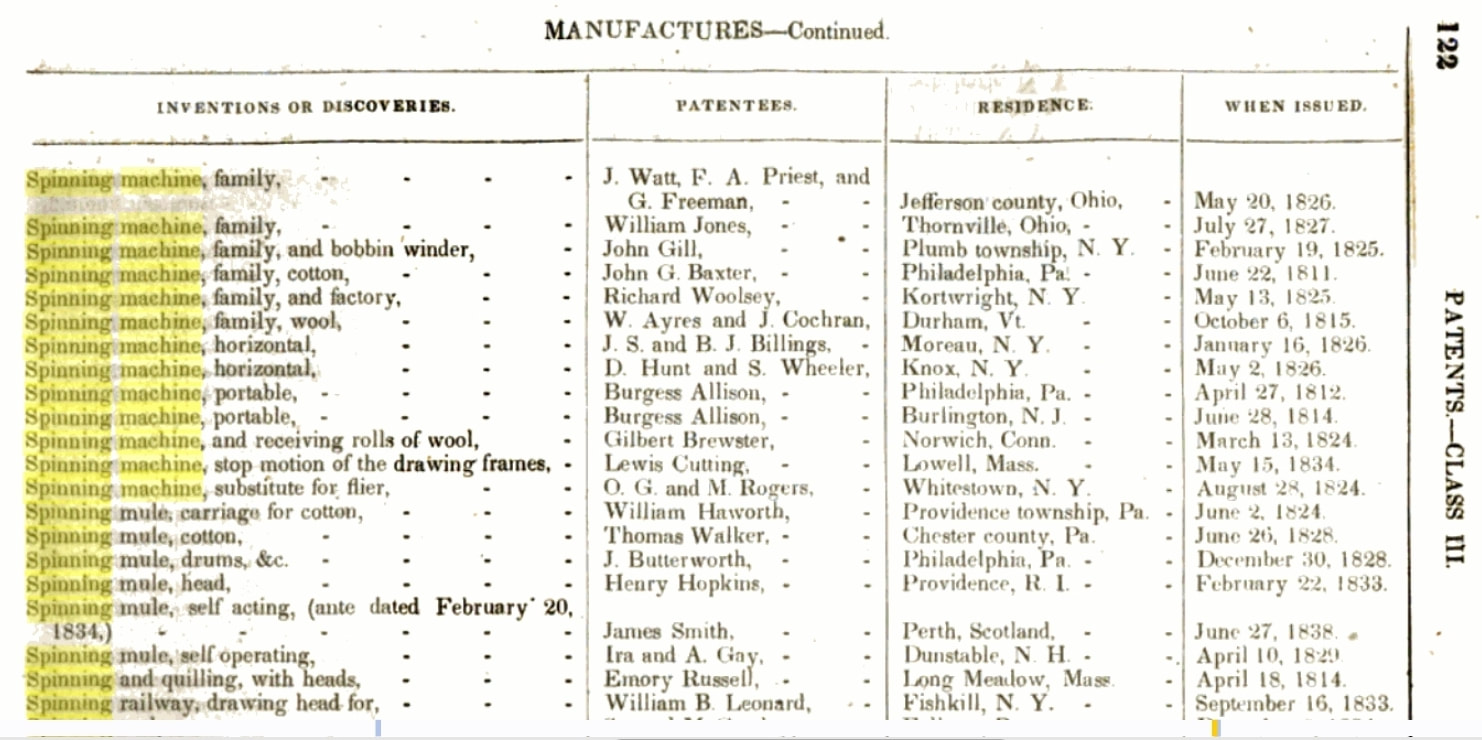

Happy New Year everyone! With the ice and snow in the first week of 2021 making for less than ideal driving conditions and Covid lockdown measures removing most travel, it hasn't been possible to transfer the Spinning Jenny from my Joiner's workshop to Cosy Yeti HQ yet. But, after some minor adjustments and tinkering, I'm excited to say it is now finished. WOOHOO! With some careful planning, I really hope that tomorrow is the day it will finally make the trip! So I thought I would put together a blog post about my process up until now, to outline the considerable work that has gone into bringing back an obsolete machine with so much potential. Spinning wool by hand is a slow business. Using a traditional spinning wheel to turn sheep's fleece into yarn, I have been limited for years to spinning only one thread, or end, of yarn at a time. Exactly like the hand spinners of centuries past in the same position as me, I needed to find a way to increase production, in order to make the process more feasible as a modern business. So what is a wool spinner to do? Well, I could buy modern industrial machinery. But I have neither the money nor the space, and it goes against my driving principle of retaining and proving the value of highly skilled hand craft. Could there be a solution to my problem that lay in the years between the 15th Century machinery I use now and the technology of today? The Spinning Jenny is a machine very nearly lost to the mists of time, it's an anachronism, totally out of sync with modern life, it only crops up nowadays as the subject of the occasional school History project. But the thing is it did exactly what I needed a machine to do. So my research began. I scoured the internet, I visited libraries (remember doing that?) and started email conversations with museums. I thought I was getting a pretty good idea of what a Spinning Jenny looked like and how it operated. Some drawings and paintings (and even the plans for Hargreaves' first Patent) are available online. But good technical details are infuriatingly hard to come by. Englishman James Hargreaves (or was it really his colleague and fellow inventor, Thomas Highs?) is credited with inventing the first machine capable of spinning multiple ends of yarn at the same time in 1764, but his was not the first machine to do so: "As early as 1678 a patent was taken out for a device to improve the productivity of spinners, but like other inventions it proved still-born." - G.D. Ramsay, The English Woollen Industry 1500 - 1750. This kind of reference cropped up time and again during my research, tantalising details about machines, but no evidence! Leonardo Da Vinci even sketched plans for a machine capable of spinning more than one thread at once. This is when the difficulty of this project hit me. Finding an original Jenny that worked (or needed restoring) was so unlikely as to be out of the question. (But if anyone has one tucked away in an ancient barn somewhere, please contact me!) There is so little information out there, despite the Jenny's historical significance. Imagine how many spinners, tucked away in the corner of a barn somewhere in Holland, Ireland, the States - anywhere - built their own wool spinning machines, tinkered with them, tweaked their operation to suit their own tastes - built up a wealth of understanding and skill about jenny spinning - then moved on, abandoned it for other work, died - their invention left to rot and eventually broken up for firewood by the next generation. It must've happened countless times. Which just goes to show why I always emphasize the importance of maintaining and valuing hand craft while the skills are still in our hands. To lose them would make us less capable as a people, and make our culture the poorer for it. I was getting excited by this idea of operating a Spinning Jenny, but there was a problem - Cosy Yeti HQ is not big enough to accommodate the machines in the drawings I was looking at online, like this: Then I stumbled upon Edward Lamson Henry's painting; "Spinning Jenny" in which an upright, North American Jenny from the mid-late 19th Century is shown. The crucial difference between Hargreaves' Jenny (and the subsequent descendants of it) and the one shown here, is that here the yarn (when the machine is actually in use) is being spun vertically, not horizontally. This was new to me... This drawing depicts another Spinning Jenny, in which the yarn is spun vertically, and gravity is used to wind the spun ends into cops at the base of the machine, closest to us. Jennies, it seemed, did not all look alike. A deep dive into the US Patent Office records followed, and revealed hundreds of patents granted to American inventors who developed a whole range of similar machines, mostly between 1800 and 1860: Think about those years, the middle of the 19th Century - long after the spinning mule and the water frame had been invented and improved and, according to most records, made the jenny obsolete - incidentally, as far as I can tell, the same is true of British patent records, they're just more difficult to access online. Why were so many people patenting "family" or "home" spinning machines in the 19th Century? Perhaps the Spinning Jenny had a part to play yet: ...the assumption that it was a domestic machine which was quickly superseded by Crompton's mule is entirely erroneous. [...] there was no haste to use this costly machine for spinning the coarse threads produced by the comparatively inexpensive jenny. [...] Because it was driven by hand and because it was easier to make or far cheaper to buy than either the mule or the water frame, the jenny was chosen by many men who set up in business with limited capital. Limited capital certainly sounded familiar, and the fact that upright jennies had been successful in the past gave my ideas a serious confidence boost. If I was going to become a Jenny Spinner, I would have to make it for myself.

Knowing that my woodwork is fairly basic and that machine workings, however basic, need to be fairly precise, I contacted a Carpenter & Joiner that I know, based at the other end of Shropshire to me, upon whose expertise I have relied for the bulk of the construction according to my design. Now all that remains is to transfer the machine in parts to HQ, put it together (and learn to use it!) and the British Isles will finally have a commercially active Jenny Spinner again. I hope! Incidentally, in looking for the most recent record of a Jenny in use in the UK, the best I've found so far is a photograph (photograph?! I know, modern right?) of the famous "Trowbridge Jenny" in use in the 1930s I believe. Was that the last time a Spinning Jenny was used in the UK? Like so many of the old ways, Jenny Spinning was probably carried on until sometime between the World Wars, somewhere in a rural parish. The investigation goes on... Watch this space!

1 Comment

While the progress of constructing our own Spinning Jenny comes excitingly close to completion, I've been hunting down anything I can find about the Jenny in any of its versions, and the people that operated them, in the hope of gleaning something useful about their craft as I attempt to become one of them!

There remains now only tantalizing glimpses into the lives and daily work of the Jenny spinners. One of the best resources I have found so far is a book entitled 'James Hargreaves and the Spinning Jenny' by C. Aspin & D. Chapman - and whilst it is scant on the technical working detail of the machinery or the subtleties of the techniques employed (which seem to be truly lost to the ages), it does feature some wonderful anecdotal stories from inside the "Jenny Shops" as workshops of spinners operating jennies were called around the early 19th Century. One passage in particular reads: "A jenny shop, says Greenhalgh, was almost as good a place to gather news as a barber's shop, particularly as the machines were not noisy. He recalls a discussion aroused by the news that Stephenson had built a locomotive, and the incredulity it aroused among the spinners. They came to the conclusion that it was an impossibility to run carriages without horses and one spinner in the heat of the debate cried out, "What, cast-metal horses gooin' to be made to run i' th' streets! Ha'd a soon believe that cast-metal men would be made to spin cops!*" And he gave one of his best draws and put up his carriage again with a flourish as if to say "Let one of your cast iron men do that". A discussion such as that would have been impossible in most of the big cotton mills in which talking out of turn was often punished with a fine. " (' James Hargreaves and the Spinning Jenny' by C. Aspin & D. Chapman, Helmshore Local History Society, 1964 ) * A cop being a compact, wound package of spun yarn. Hi everyone!

Welcome to the start of a brand new blog, preparing for the start of an exciting new year and, despite Covid-chaos, 2021 promises to be full of new developments here at Cosy Yeti. Through the blog I want to invite any of you that are interested in my work into Cosy Yeti HQ here in beautiful Shropshire. I want this to be a chance to shine a light on the traditional processes I use every day in more detail than social media allows - the pitfalls and frustrations of working with very old technology just as much as the successes! Stay tuned to the social media in coming weeks, there are some exciting works in the pipeline. Stay safe and stay in touch! Toby. |

AuthorToby Tottle - Wool Spinner & Hand Weaver Archives

January 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed